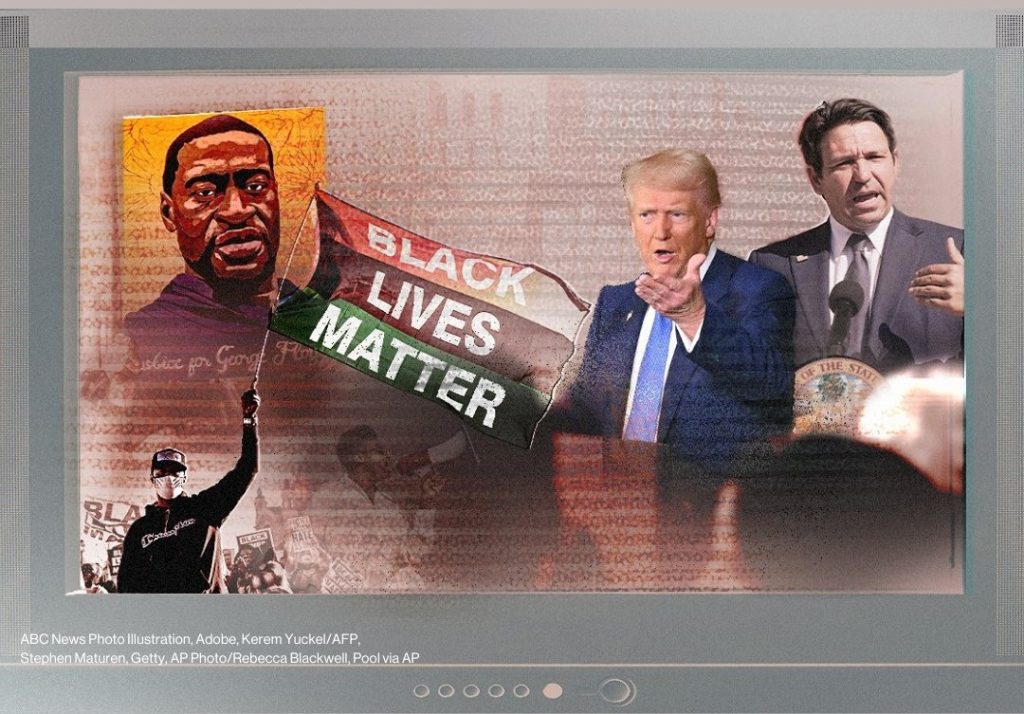

Media framing of racial issues has changed since the George Floyd protests.

By Erika Franklin Fowler and Neil Lewis Jr., 538

Almost five years ago, in the immediate aftermath of the murder of George Floyd, there was a brief window in which Americans seemed committed to opposing racism in all its forms. Individuals bought books to educate themselves about past injustices; companies pledged hundreds of billions of dollars to efforts to address those injustices; even the federal government pledged to use its powers to advance equity for all. Multiple surveys at the time found a dramatic increase in support for racial justice movements and overwhelming agreement that racism and discrimination were a “big problem.”

Those efforts and sentiments did not last. Instead, the brief wave of racial progress in the early 2020s has been countered by successive waves of counter-messaging starting in 2021 that has escalated into a tsunami of policy backlash in 2025. A plurality of voters in the last presidential election supported the candidate who openly campaigned on racial animus (particularly in his unscripted messaging); companies and other organizations have reversed course on their commitments to advancing diversity, equity and inclusion; and President Donald Trump has even issued an executive order to ban such efforts in the federal government.

We have been tracking this shift in public discourse toward racial equity as it has unfolded over time. Our research team has been monitoring not only (anti-)DEI efforts, but also how the media has been covering those efforts. As social scientists interested in the role that media plays in public discourse as well as social policy, we have spent the past five years — from January 2020 to January 2025 — carefully studying how television news stations have been covering stories about racial equity in the U.S.

There are 210 different television markets in the U.S. In each of those areas, local news reporters share stories that highlight the major issues of the day and provide media frames that shape how viewers think and talk about those issues. Importantly, local stations and reporters share this content beyond their televised broadcasts, disseminating video and links online and through their social media channels as well.

Utilizing data from TVEyes available to us through the Wesleyan Media Project, our team was able to analyze five years’ worth of news coverage to determine how news stations were covering racial equity issues. Drawing on closed captioning from all local news broadcasts airing on television stations affiliated with ABC, CBS, Fox, NBC and PBS, we used keyword searching to identify relevant stories and then natural language processing to further analyze the content of the stories themselves.

Then, media coverage took a turn and began focusing on strategic counternarratives that undermined those racial equity initiatives. From early 2021 through early 2023, instead of focusing on structural racism, coverage shifted to criticisms of “critical race theory.”

To be clear, critical race theory has a specific meaning in academic discourse — it is a body of scholarship that examines the role of racism in the American legal system. But that meaning is not what the media was covering. Instead, coverage focused on critical race theory as Republicans redefined it — in the words of conservative activist Christopher Rufo, “the entire range of cultural constructions that are unpopular with Americans.”

The final frame that took over media coverage was DEI. Although some of this coverage described positive initiatives in local communities to increase diversity and belonging especially early in the timeline, the bulk of the coverage in 2023 and 2024 revolved around attention to bans and other rollbacks or closures of DEI programs and hiring activities in state agencies and universities.

Why does media framing about racial equity matter? Because of the role that the media plays in how people interpret news and events to make sense of the world. Media coverage tends to be a reflection of both the rhetoric espoused by political and social elites and the changing attitudes of the society. Especially in today’s polarized and fragmented media environment, local news remains particularly influential because its audiences are still large and, importantly, it is still viewed positively and trusted by audiences from both parties.

Because of this influence, when the media tells stories, the ways that they frame those stories can affect how people think and feel — even the policies they support. For example, political scientists have conducted experiments that found that racially coded stories about social policies, such as welfare, can activate feelings of racial animus that in turn undermine support for those policies.

When media outlets amplify racially inflammatory rhetoric, that, too, affects viewers. Another group of political scientists conducted a survey experiment to measure how hearing Trump’s inflammatory campaign rhetoric affected everyday citizens. They found evidence of an “emboldening effect” whereby citizens who hear political elites using prejudiced language became more likely to both express and act upon their prejudices themselves. These processes end up fueling what a team of political psychologists have recently called “trickle-down racism“—when people get the message that prejudice is socially acceptable, it normalizes racism among the broader population.

These broader processes are why recent attacks on DEI — and the media’s coverage of those attacks — matter for society’s ability to achieve the racial equity goals that were prominently professed over the past five years. As the attacks on DEI initiatives have increased over the last few years in an attempt to decrease support, there is some evidence that those messages may be meaningfully changing public opinion. For instance, the share of U.S. workers saying that focusing on DEI at work is a good thing has declined. That decline is important to put into its proper context, however: The majority of Americans still favored such initiatives, and fewer than one-third of Americans in a late January 2025 YouGov survey said they had an unfavorable view of DEI programs.

Despite that public support, some commentators have suggested that talking about racial equity actually sets the cause back. Our recent research suggests that conclusion may be premature. In recent nationally representative survey experiments, we have found that some ways of discussing these issues — such as emphasizing the benefits of DEI initiatives and their effectiveness — bolsters support for equity-enhancing policies. That suggests, even in these politicized times, that all is not lost for the racial equity movement.

.

.

Be the first to comment